Drug companies are exploiting rare mutations that make one person nearly immune to pain, another to broken bones

Caroline Chen

Steven Pete can put his hand on a hot stove or step on a piece of glass and not feel a thing, all because of a quirk in his genes. Only a few dozen people in the world share Pete’s congenital insensitivity to pain. Drug companies see riches in his rare mutation. They also have their eye on people like Timothy Dreyer, 25, who has bones so dense he could walk away from accidents that would leave others with broken limbs. About 100 people have sclerosteosis, Dreyer’s condition.

Caroline Chen

Steven Pete can put his hand on a hot stove or step on a piece of glass and not feel a thing, all because of a quirk in his genes. Only a few dozen people in the world share Pete’s congenital insensitivity to pain. Drug companies see riches in his rare mutation. They also have their eye on people like Timothy Dreyer, 25, who has bones so dense he could walk away from accidents that would leave others with broken limbs. About 100 people have sclerosteosis, Dreyer’s condition.

Both men’s apparent superpowers come from exceedingly uncommon deviations in their DNA. They are genetic outliers, coveted by drug companies Amgen, Genentech, and others in search of drugs for some of the industry’s biggest, most lucrative markets.

Illustration: Stephanie Davidson

Their genes also have caused the two men enormous suffering. Pete’s parents first realized something was wrong when, as a teething baby, their son almost chewed off his tongue. “That was a giant red flag,” says Pete, now 34 and living in Kelso, Wash. It took doctors months to figure out he had congenital insensitivity to pain, caused by two different mutations, one inherited from each parent. On their own, the single mutations were benign; combined, they were harmful.

Dreyer, who lives in Johannesburg, was 21 months old when his parents noticed a sudden facial paralysis. Doctors first diagnosed him with palsy. Then X-rays revealed excessive bone formation in his skull, which led to a diagnosis of sclerosteosis. Nobody in Dreyer’s family had the disorder; his parents both carried a single mutation, which Dreyer inherited.

Dreyer and Pete are “a gift from nature,” says Andreas Grauer, global development lead for the osteoporosis drug Amgen is creating. “It is our obligation to turn it into something useful.”

What’s good for patients is also good for business. The painkiller market alone is worth $18 billion a year. The industry is pressing ahead with research into genetic irregularities. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is expected to approve a cholesterol-lowering treatment on July 24 from Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals based on the rare gene mutation of an aerobics instructor with astoundingly low cholesterol levels. Amgen has a similar cholesterol drug, based on the same discovery, and expects U.S. approval in August. The drugs can lower cholesterol when statins alone don’t work. They are expected to cost up to $12,000 per patient per year and bring in more than $1 billion annually.

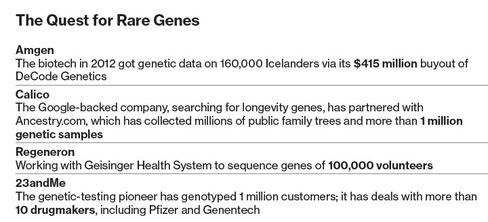

Drugmakers are also investing in acquisitions and partnerships to get their hands on genetic information that could lead to more drugs. Amgen bought an Icelandic biotechnology company, DeCode Genetics, for $415 million in 2012, to acquire its massive database on more than half of Iceland’s adult population. Genentech is collaborating with Silicon Valley startup 23andMe, which has sold its $99 DNA spit kits to 1 million consumers who want to find out more about their health and family history—more than 80 percent have agreed to have their data used for research. The Genentech partnership will study the genetic underpinnings of Parkinson’s disease. And Regeneron has signed a deal with Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Health System to sequence the genes of more than 100,000 volunteers.

Underlying this is the plummeting cost of gene sequencing. It took $3 billion and 13 years, from 1990 to 2003, to sequence the first human genome. The cost today is as low as $1,000 a patient, making it viable to sequence large numbers of people and discover relationships between genes and symptoms.

The researchers who study outliers are often the first to realize the potential power behind a mutation. In 2010, Socrates Papapoulos, a professor of medicine at the Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands, visited an isolated Dutch community where much of the population had overgrown skulls and abnormally large bones. At a town meeting, he asked if anyone had been in a major car accident. One man raised his hand. “He said, ‘I was crossing the street with my brother, and a Mercedes was coming, and I didn’t have time to move,’ ” Papapoulos says. “And I said, ‘What happened?’ and he said, ‘You should have seen the Mercedes.’ ”

Amgen realized that if researchers could mimic the effects of the genetic mutation, they could encourage bone growth strong enough to counter osteoporosis. People with sclerosteosis lack a protein that acts as a brake on bone growth. Without that protein, bones grow abnormally thick. It stood to reason, researchers thought, that a drug that could block the protein in patients with osteoporosis would encourage bone regrowth.

Amgen’s scientists created hundreds of antibodies that they tested to determine which might be able to get in the way of the protein. It took them three and a half years of research before they were able to identify the best antibody to inhibit the protein. Then NASA came calling.

In 2010 the space agency, preparing for its final space shuttle mission, was looking for promising research projects. It invited Amgen to test the drug’s ability to stop the loss of bone mass often seen during spaceflight. Amgen sent 30 mice on the Atlantis shuttle. Half got the drug, romosozumab. After 13 days, the injected mice had gained bone mineral density as the control group’s bones weakened.

Amgen has run two human trials since 2006. It is conducting two final-stage trials, with the first batch of results expected in early 2016. If the drug works as well as promised, it could bring Amgen $1 billion to $2 billion in sales per year, says Cowen Group analyst Eric Schmidt.

Illustrator: Stephanie Davidson

Unlike sclerosteosis patients, people such as Pete who don’t feel pain have no outward physical features that give them away. Instead, researchers have stumbled upon them more or less by chance. A research article on families in Pakistan came after the discovery of a 10-year-old boy who as a street performer stabbed himself with knives and walked on burning coals.

Xenon Pharmaceuticals, a small Canadian biotech, started studying more than a decade ago families who showed similar pain-free traits and tracked down the gene responsible, which regulates a pathway in the body called the Nav 1.7 sodium ion channel. With just a few dozen employees, Xenon turned for development help to Genentech, which is owned by Roche, and its 1,200 research and development scientists.

“The beauty of the phenotype is that you’re largely normal,” says Morgan Sheng, Genentech’s vice president for neuroscience, referring to how the genes are manifested in an individual. “You want to just prevent pain and not cause a bunch of other problems,” he says. The only other effect typically seen is a loss of the sense of smell.

The promise of the Nav 1.7 channel is to create an entirely new class of painkiller. Options on the market are all problematic. Opioids, such as morphine, are addictive, while nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, are ineffective with severe pain and can cause gastrointestinal side effects including bleeding. Genentech is still in the earliest stage of clinical trials, and it could take more than five years before a drug is released.

While outliers may hold the secret to curing the ills of the rest of humanity, there is no profit motive to find treatments for their aberrant sufferings. The market is too small, even though their suffering is real. Pete’s left leg is permanently damaged from years of injuries he couldn’t feel, and he lives with the anxiety that he could overlook a severe illness, such as appendicitis, whose major symptom is pain. He regularly participates in research studies and says he wants to contribute to scientists’ knowledge to help them develop better painkillers. “Before a lot of us participated in these projects, very little about pain itself was known,” he says.

Excessive bone growth in Dreyer’s skull has led to multiple operations to relieve pressure on cranial nerves and the brain, though ultimately the surgeries were unable to prevent hearing loss.

Dreyer, a Ph.D. student in paraclinical science at the University of Pretoria, isn’t waiting for Big Pharma to come to his rescue. For his Ph.D. project, he’s researching treatments for his own disease and hopes to raise 2 million rand ($162,000) to fund his work. “There are thousands of people suffering from osteoporosis, so developing a treatment for them is great,” he says. “That being said, I do think it would be nice if they could help us out now that they understand our disease and are able to use it for their treatments.”

The bottom line: Genentech and Amgen are studying rare gene mutations to create blockbuster drugs for pain and osteoporosis.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий